So, since I’ve done Introductions part one and two, logically I should be doing part three, which is all about the research side of this project. I’m going to have to have a brief departure from this logical flow, however, so that I can talk about practice-based research and therefore help that third part make more sense to people not in my head or research area. I guess you could consider this a kind of Introductions (part 2b)? Since I can’t help but ramble on about the research I’m doing, it seems like a good idea to explain a bit about how I’m doing it. And hey, maybe I’ll inspire some other people to try it out (or at least collate a small but handy list of resources for students who try to forget the research part of practice-based research).

What is practice-based research (PBR)?

Since this is a more academic-related topic, let me pull up an academic-y explanation.

“Practice-based Research is an original investigation undertaken in order to gain new knowledge partly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice… Whilst the significance and context of the claims are described in words, a full understanding can only be obtained with direct reference to the outcomes.”

Candy, 2006

Basically, PBR is a form of research where the knowledge generated from your research comes from doing the practice (in my case, creative writing). Your critical side (aka, the dissertation) is tied to the creative output – you wouldn’t get there without actually doing the creative practice. There are a few different terms along the same vein that get used almost interchangeably – arts-based research, art-as-research, practice-led research, for example – but I use PBR because my research is based in the practice and I wouldn’t get the same understanding without it. (If you want an example of practice-led research, I really enjoyed reading Donna Lee Brien‘s paper detailing her experience of writing a biography, as it helped make the distinction between practice-based and practice-led research clearer and let me reflect on what elements of my own creative process could be considered practice-led)

How do you do PBR?

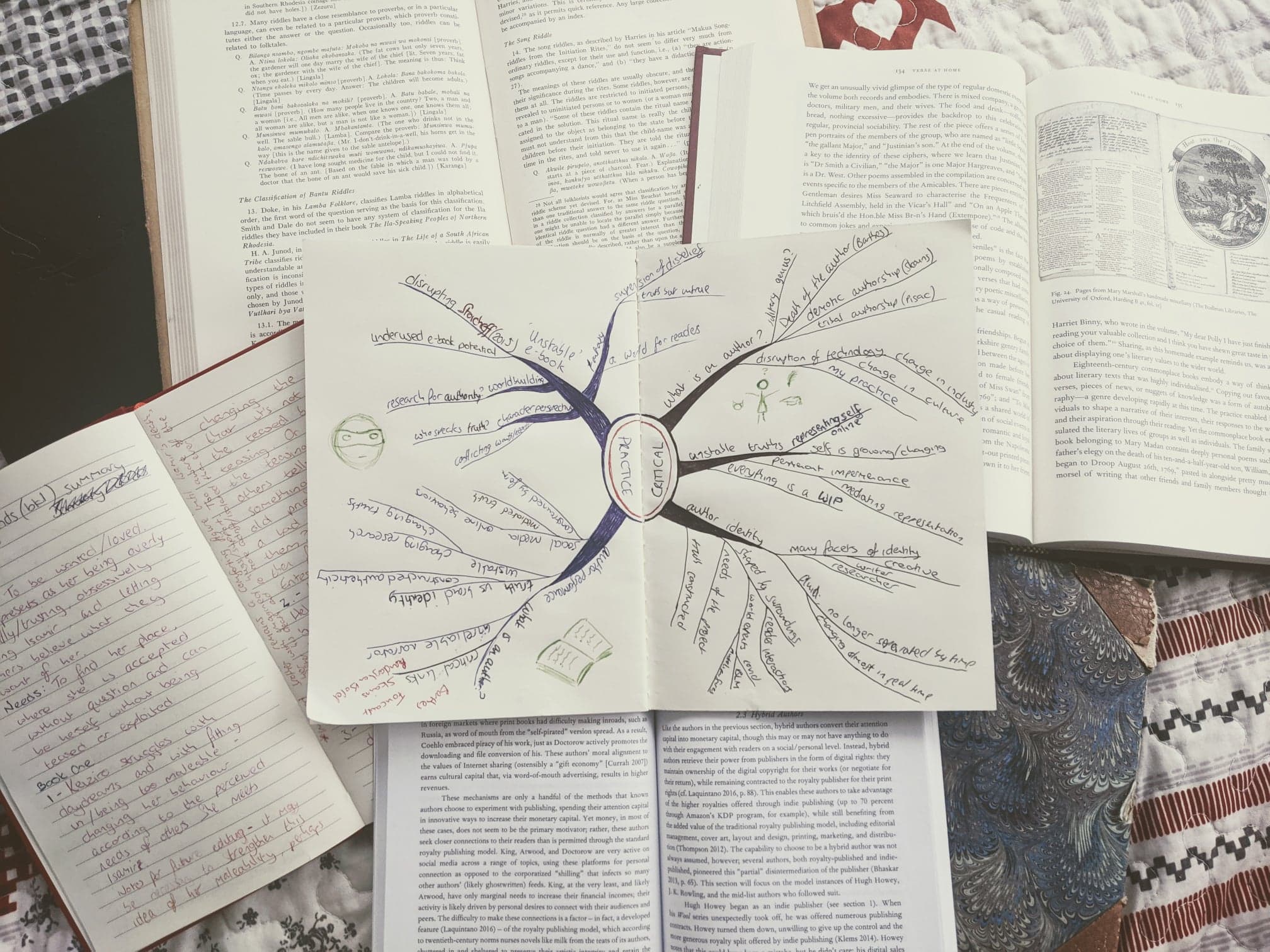

Because there are lots of ways to do practice – whether it’s art, design, music, writing, etc – there’s no fixed way to do it. I personally like the model Skains provides (yay, clear figures!), but I also found some use in Kerrigan and McIntyre‘s paper (example research questions!) and Candy and Edmonds (example frameworks!). Is it obvious that I like examples? Most articles on the subject give guidelines, highlighting good practices or explaining what PBR needs to be considered research or worthy of doctoral study, but they all generally emphasise the need to be flexible so that adjustment can be made for the type of practice at the centre of the research. My own methodology draws heavily on the sources I’ve highlighted, adjusted to suit my particular project and the aims I have with it, but the basic gist of it is think of an issue (in my case, I initially wanted to investigate why authors don’t take advantage of the fact e-books are changeable?), do some research, revisit the research question (endlessly), start doing the practice and more research, start making arguments, write the dissertation, and always, always, be ready for things to go off in a direction you didn’t expect.

The other big common thing in articles about PBR is the need for a research log. There’s a need to be able to record your thoughts and experiences as you go along. Since thinking you’ll be able to retrospectively remember why you decided to do x and y months later is just suffering waiting to happen, this is definitely something I agree with. I barely remember why I make decisions with my research log – how I’d function without it, I have no idea! I mean, I still have the issue that my focus changes as time goes on and what I think is important now may not have seemed important three months ago (and I hate past me for it) but at least it’s a little less torturous.

What must PBR do?

Drawing again from that great guide by Linda Candy, there needs to be a goal – research questions that need to be answered, objectives that need to be met – and it must be clear why those questions are being asked and how this contributes to knowledge. And, of course, it must be clear how the methods used help answer the research question(s) and why that method was chosen. So, much like other forms of research, there’s got to be something that needs to be found out, a reason that knowledge is wanted or needed, and an argument for why you’ve chosen to do whatever method you’ve chosen is the best one.

In my case, the practice part of my PhD is both creative output and performance. The Shifting Sands e-book and the online performance of authorship (as truthful as I aim for this performance to be, it is inescapably a performance of some kind). The rationale behind this practical aspect is that I will gain more understanding of how authorship is affected by the innovation(s) I’m playing with. By creating an “unstable” e-book and self-publishing it, I get an insider’s perspective of what it is to be an author online and experimenting with what an e-book could/should be. I could have used ethnographic methods, and maybe interviewed some writers of e-lit, but there’s such a wealth of e-lit forms that one author’s experience may differ hugely from another’s. And, as I’m very much experiencing now with the launch of this website, there are things I wouldn’t ever have thought of as being relevant without actually doing the practice. I really value the fact that I am able to do this kind of research (even if it is sometimes frustrating).

You mention frustrations – pros and cons of PBR?

Okay, so since I’d rather end with a positive, let’s go with cons first.

Cons

- You constantly feel like you’re being pulled in opposite directions. I don’t know about other practice-based researchers, but I always struggle to focus on both the practice and the critical side at once. They have to take turns being the focus of my time because I just do not have enough head space to have them both at the front at once. That’s not to say I don’t think of the other one while it’s not the focus – the creative is getting a lot of my attention at the moment, but my research log is constantly getting new thoughts for the critical added based on my experiences with the creative – it’s just that I tend to work best if I work in chunks. This chunk is creative-focused, working on this website and editing the book, but the one before that was critical as I worked on some content analysis, and then before that it was drafting up my methodology. Do I occasionally feel like I’m cheating on one half when I’m working on the other? Yes. (Other practice-based researchers, do you get this too?!)

- Not gonna lie, sometimes the practice feels a bit like it’s in the way. I find a thing I really want to dive in and research, but then how does it fit with the practice and how will I actually cope with it in my word count and on my plate? I often feel like life would be simpler if I was just doing the critical side. But then I have to remember that I find these little tunnels of research because of the practice. I don’t think I’d be half as interested in the language authors use on Twitter, or the shadier dealings of Amazon if it wasn’t for the practice. It’s just a side of PBR I have to deal with.

- And, on the more academic side of cons, it’s based largely on the experience of one researcher so not necessarily something that could be easily generalised. My practice-based research into authorship is always going to be influenced by the fact I’m doing this as part of my PhD, or the events of this past year, or some unrecognised aspect of my childhood. But, despite such a limitation, there are some great strengths too.

Pros

- Obviously, as I’ve mentioned above, you get a really good inside view of your research. It’s not just observed knowledge, it’s experienced. Because of this, you learn a whole lot about your practice, but also a whole lot about yourself. Nothing quite like having to keep a research log to make you have to reflect on why a particular aspect of your research is triggering your impostor syndrome!

- It’s flexible. I really like how Skains phrased it in her 2018 paper, so I’ll quote it here:

“PBR is often a process of exploration and discovery, with many key insights arriving via serendipity, rather than as part of experiment design. Thus, the initial research question is often vague and typically open-ended, to permit flexibility in the practice and space for such serendipitous discoveries to occur.”

Skains, 2018

Basically, the map is blurry and the muses regularly intervene. I’m a visual person so I like to think of PBR as kind of being like a mad scientist in a white lab coat and a bunch of coloured test tubes in front of me. I know vaguely what might happen when I mix some of them – red and yellow making orange, for example – but there are some unknowns at play. I don’t know which ones will go *BOOM*, or what other reactions could go on, only that something is most likely going to happen. So I frame my research question based on what I think I’m researching and set off on my journey. Sometimes, as detailed in Skains’s article, the research questions stays the same. Other times, as with my master’s research and, I expect, with this PhD project, things end up looking vastly different than you first thought. In short, the muses are loud when you’re doing PBR, and nobody labelled their test tubes, so it lets you be flexible to make up for the unexpected bits.

3. It’s fun. Like, I wish I could be more academic in my argument here, but there’s no other way to explain it. Who else gets to spend their time writing a messed up e-book, publishing it, and then getting to research why things happened that way? I’m not saying it’s not hard work – believe me, soooo much goes into this – but I love what I do. Yeah, I get frustrated that I can’t map out exactly how things are going to look in a years time, and I constantly feel like I’m playing catch-up with either the critical or creative halves, but I am never bored. There’s too much to do and I’m interested in all of it.

So, TL:DR version, practice-based research is a form of research where doing the practice is what fuels the research part. It’s frustrating at times, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.